Gene Therapy and Drug Interactions: Unique Safety Challenges

Jan, 5 2026

Jan, 5 2026

Gene Therapy Drug Interaction Checker

Gene therapy promises to fix diseases at their root-by correcting faulty genes instead of just managing symptoms. But behind this breakthrough lies a hidden danger: how these treatments interact with everyday medications. Unlike pills or injections, gene therapies don’t wear off. They change your cells permanently. And that permanence creates risks no drug has ever faced before.

Why Gene Therapy Isn’t Like Other Drugs

Most medications work temporarily. You take a statin, it lowers cholesterol for a few hours. You take an antibiotic, it kills bacteria until it’s cleared from your body. Gene therapy is different. It delivers new genetic instructions into your cells using engineered viruses-usually adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) or lentiviruses. Once inside, these vectors insert or replace genes. The changes can last years, even decades. That’s powerful. But it also means side effects can show up years later.In the late 1990s, a young boy named Jesse Gelsinger died after receiving gene therapy for a rare liver disorder. His body reacted violently to the adenovirus vector used to deliver the gene. His immune system went into overdrive, causing multiple organ failure. The same vector had already killed two monkeys in preclinical tests. That tragedy forced scientists to rethink everything. Now, we know viral vectors aren’t just delivery trucks-they’re biological triggers.

When Your Immune System Attacks the Therapy (and Your Medications)

Your immune system doesn’t distinguish between a harmful virus and a therapeutic one. If it detects the viral vector carrying your new gene, it may launch a full-scale response. This isn’t just a fever or swollen lymph nodes. It can trigger massive inflammation, liver damage, or even septic shock.Here’s the scary part: that same inflammation changes how your body handles other drugs. The immune system releases cytokines-signaling molecules-that can turn up or down the activity of liver enzymes called cytochrome P450. These enzymes break down over 70% of all prescription drugs, from blood thinners to antidepressants. If gene therapy suppresses CYP3A4, your statin could build up to toxic levels. If it boosts CYP2D6, your painkiller might stop working entirely.

There’s no way to predict this for each patient. One person might have a mild reaction. Another, with the same therapy, could develop life-threatening drug toxicity. There are no standard guidelines yet. Doctors often don’t know which drugs to pause, adjust, or avoid after gene therapy.

Off-Target Changes That Alter Drug Metabolism

Gene editing tools like CRISPR aren’t perfect. They can accidentally cut DNA in the wrong place. This is called off-target editing. In some cases, those mistakes happen in liver cells-the same cells that produce enzymes to process drugs.Imagine a gene therapy meant to treat sickle cell disease edits a gene in bone marrow cells. But somewhere, it also nicks a gene in a liver cell that controls how your body breaks down warfarin. That patient could start bleeding internally without warning, even if they’ve been on the same warfarin dose for years.

Even more concerning: some gene therapies use modified cells grown in the lab, then reinfused into the patient. These cells might migrate to organs they weren’t meant to reach. A cell meant to repair heart tissue could end up in the gut and start producing a protein that interferes with absorption of oral medications. These aren’t theoretical risks. They’ve been observed in animal studies-and could appear in humans as more therapies roll out.

Long-Term Monitoring Isn’t Optional-It’s Mandatory

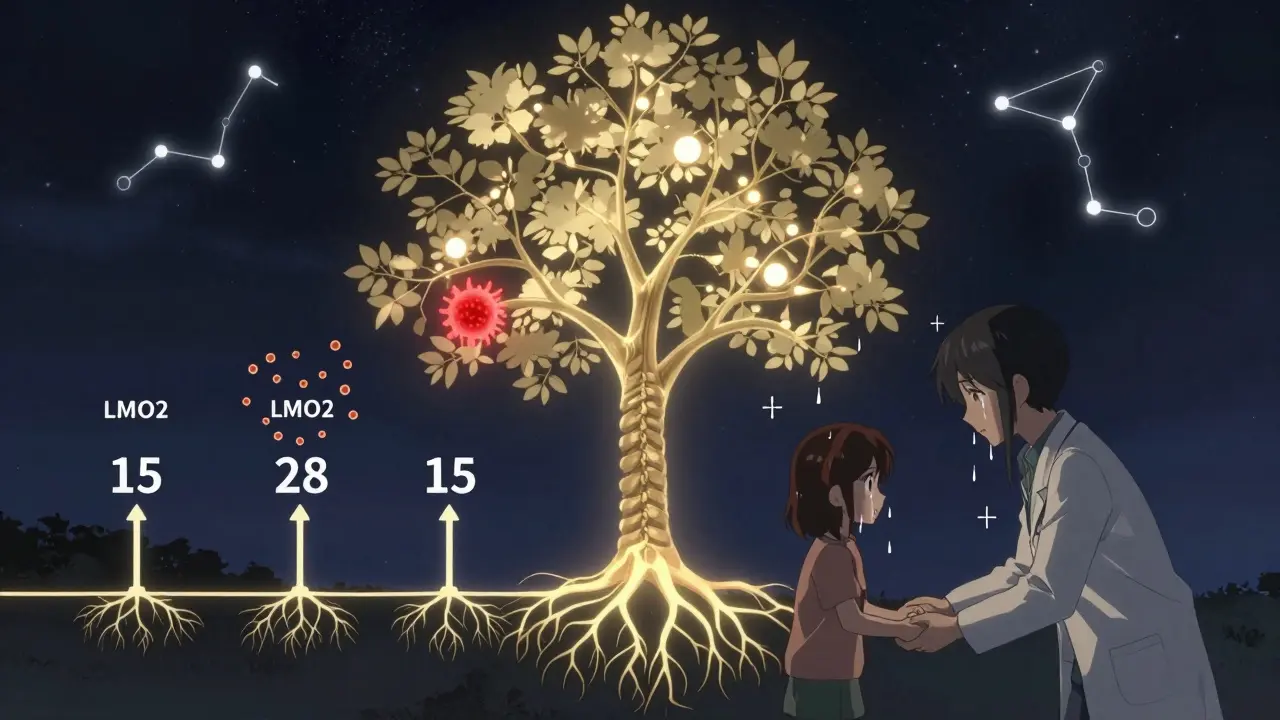

The FDA requires 15 years of follow-up for gene therapies that integrate into the genome. Why? Because cancer can take years to develop. In the early 2000s, five children treated for SCID-X1 (a severe immune disorder) developed leukemia. The therapy inserted the corrective gene right next to a cancer-promoting gene called LMO2. It took 2 to 5 years for the cancer to appear.That’s not a one-off. Any gene therapy that permanently alters DNA carries this risk. And if that altered DNA affects how your body metabolizes drugs, the danger grows. A patient might be fine for 10 years-then suddenly, a common painkiller triggers liver failure because their gene therapy changed how their CYP enzymes work.

Right now, there’s no database tracking these delayed interactions. No system flags that a patient received gene therapy when they walk into a pharmacy. Doctors don’t routinely ask. That’s a gap with deadly potential.

Viral Vectors Can Spread-And So Can the Risk

Some gene therapies use viruses that can still replicate slightly, even after being modified. The FDA requires companies to prove their vectors won’t spread to family members. But what if they do?Imagine a father gets an AAV-based gene therapy for hemophilia. A week later, his toddler catches a cold-and gets exposed to the viral vector through saliva or nasal secretions. The child, who never consented, now has a foreign gene in their liver. They’re unknowingly carrying a biological agent that could interact with future medications. There’s no way to monitor or reverse this. And it’s not science fiction. Cases of vector shedding have been documented in clinical trials.

AAV Therapies: The New Normal With Hidden Risks

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are now the most common delivery system. They’re less inflammatory than older vectors. But they’re not harmless. Different AAV serotypes target different tissues. AAV9 goes to the brain and heart. AAV8 targets the liver. AAV5 prefers the lungs.That means the drug interaction risks change depending on the vector. A patient on AAV8 therapy for a liver disease might have altered metabolism of drugs processed by the liver-like anticoagulants, antifungals, or certain chemotherapy drugs. A patient on AAV9 for spinal muscular atrophy might have changes in how brain-penetrating drugs behave. We’re still mapping these patterns.

And here’s another twist: many people already have antibodies to AAVs from past infections. That means the therapy might not even work. Or worse-it could trigger a stronger immune reaction when given with a drug that also affects immunity, like a biologic for rheumatoid arthritis.

What’s Missing: The Data We Don’t Have

We don’t know how gene therapy interacts with most common medications. There’s no list of safe or unsafe combinations. No pharmacokinetic models. No clinical guidelines. Even the big pharmaceutical companies are flying blind.Right now, most gene therapy trials exclude patients on chronic medications. That’s safe for the trial-but it leaves real patients in the dark. A 65-year-old with Duchenne muscular dystrophy might get gene therapy, but also takes beta-blockers for heart issues and statins for cholesterol. What happens when those drugs meet the viral vector? No one knows.

We need longitudinal studies tracking thousands of patients over 10, 15, 20 years. We need genetic screening before therapy to predict immune response. We need real-time monitoring of liver enzymes and drug levels. And we need a global registry that links gene therapy records to prescription histories.

The Bottom Line: More Power, More Responsibility

Gene therapy isn’t just another treatment. It’s a biological reset button. And like any reset, it can crash the system if not handled with extreme care.Patients need to know: if you get gene therapy, your body’s relationship with every drug you take could change-now or years from now. Doctors need to ask: Has this patient had gene therapy? What vector was used? What tissues were targeted? Pharmacists need to flag these patients in their systems.

Until we have better data, the safest approach is caution. Avoid new medications unless absolutely necessary. Review all current drugs with a specialist. Keep detailed records. And never assume a drug is safe just because it worked before.

The future of medicine is here. But we’re still learning how to live with it safely.

Can gene therapy cause cancer years after treatment?

Yes. In early trials for immune disorders, gene therapy inserted therapeutic DNA near cancer-promoting genes, leading to leukemia in some patients years later. This happened because the viral vectors used integrated randomly into the genome. Modern therapies use safer vectors, but the risk isn’t zero. That’s why the FDA requires 15 years of follow-up for integrating gene therapies.

Do I need to stop my medications before gene therapy?

Maybe. Some drugs, especially those that affect the immune system like steroids or biologics, may be paused before treatment to reduce the risk of interfering with the gene therapy vector. Others, like blood thinners or heart medications, may need dose adjustments after treatment due to changes in liver enzyme activity. Always consult your gene therapy team before making any changes.

Can my family catch gene therapy from me?

It’s possible, but rare. Some viral vectors can be shed in bodily fluids like saliva or stool for days or weeks after treatment. While most are designed to be non-infectious, there’s still a small chance they could be passed to close contacts. For this reason, patients are often advised to avoid close contact with infants, pregnant women, or immunocompromised people for a period after treatment.

How long should I be monitored after gene therapy?

For therapies that permanently alter your DNA, monitoring should last at least 15 years. This is required by the FDA. For therapies using non-integrating vectors like AAV, monitoring typically lasts 5-10 years. But even then, long-term risks like delayed immune reactions or off-target effects may still emerge. Keep all follow-up appointments and report any new symptoms, even if they seem unrelated.

Are there any drugs I should avoid completely after gene therapy?

There’s no official list yet. But experts advise avoiding new medications, especially those metabolized by the liver (like statins, antifungals, and some antidepressants), until your doctor confirms safety. Immunosuppressants and chemotherapy drugs also carry higher risk due to their effect on cell growth and immune response. Always tell every healthcare provider you’ve had gene therapy before starting a new drug.

Harshit Kansal

January 7, 2026 AT 02:52This is wild stuff. I never thought a cure could make your meds stop working years later. Doctors need to start asking about gene therapy like they ask about allergies.

Gabrielle Panchev

January 8, 2026 AT 00:37Let me just say-this is not science fiction, this is science fact, and we are not ready, not even close, not in the way we think we are-because we’re treating gene therapy like it’s a new iPhone update, when it’s actually a full-system overwrite, and if your system crashes? There’s no factory reset, no backup, no ‘undo,’ and no one’s keeping a public ledger of who got what, where, and when-and yes, I’m talking to you, FDA, you’re letting this happen without a traceable database, and that’s not oversight, that’s negligence with a side of corporate lobbying.

Vinayak Naik

January 8, 2026 AT 22:56Man, I read this and my brain did a backflip. Gene therapy’s like giving someone a new engine but not telling them the fuel type changed. Now their old gas station might blow up their car. And nobody’s got a manual yet. I work in pharma-trust me, the docs are just as lost as the patients.

Lily Lilyy

January 10, 2026 AT 21:59Thank you for writing this with such clarity. It’s scary, but knowledge is power. Let’s keep pushing for better tracking and patient education. We can do this, together.

Kiran Plaha

January 11, 2026 AT 15:29So if I get gene therapy, do I need to tell every pharmacist I ever see from now on? Even the ones at the corner store? That feels overwhelming.

Melanie Clark

January 12, 2026 AT 15:13This is all part of the big pharma agenda to control your body forever. They don’t want you to know that the virus vectors are designed to track your DNA and link to government databases. Your statin doesn’t just stop working-it’s being monitored. They’re using gene therapy to build a bio-ID system. Wake up. The FDA is in on it. They’ve known since 1999. Jesse Gelsinger wasn’t a tragedy-he was a warning they buried.

Brian Anaz

January 14, 2026 AT 03:55Why are we letting foreign scientists run these trials? India’s got no regulatory backbone. If this stuff leaks into families, it’s a public health disaster waiting to happen. We need a U.S.-only gene therapy program. No exceptions.

Saylor Frye

January 14, 2026 AT 16:20Interesting. Though I suppose if you’re not a biochemist with a PhD and a subscription to Nature, you’re just a layperson being manipulated by sensationalist science journalism. The real risk is panic, not the therapy.

Katelyn Slack

January 15, 2026 AT 04:27i think this is so important but i keep forgetting to tell my dr about my gene therapy. i had it last year and now im on blood pressure meds and i dont know if its safe. sorry for the typos, typing on my phone. anyone else have this problem?

Venkataramanan Viswanathan

January 15, 2026 AT 13:37As someone who has witnessed the evolution of medical science in both the West and India, I must emphasize: the global community must collaborate on a unified registry for gene therapy recipients. This is not a national issue-it is a human one. Without standardized tracking, we risk repeating history. The responsibility lies not just with regulators, but with every clinician, pharmacist, and patient. Let us act before the next tragedy becomes inevitable.